A Man About A Horse–ECM bio pt. 2

(Part 1, "This Album")

Electric Guitar

I started playing guitar at the age of six to get attention. My father was a union organizer in Danville, Virginia and professor of labor law at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, and he also played his 12-string to get attention. His job was to drive all over the state of Wisconsin and give evening seminars on labor law and union strategies to tired shoe and boot workers. To get their attention, and to have a little fun he would pull his guitar out of its case and they would all sing union songs. "Union Maid", "Drill Ye Tarriers Drill", and so on.

There were a lot of union and church sing-alongs at our home as well. People from the university and our church would come over and break out instruments and sing for hours after dinner. Banjos, guitars, bass, dulcimers, mandolins, whatever anyone had. It was smoky, out of tune, and fun.

Whenever my dad opened his guitar case conversations would stop. I noticed this. I notice that when someone opened up a guitar case and pulled out a guitar it was like they were have pulling a sword out of a stone. The room was magnetized. This was not lost on me, the smallest and most sports-challenged kid in school. I wanted one of those guitars, but I wanted an electric one.

My dad and I fought over this. He said he would buy me an acoustic guitar, but not an electric one. I couldn't understand why, and whined persistently for six months. Finally he said, "Well, with an electric guitar, what are you going to play at a beach party?" That stopped me. I didn't have an answer for that. I didn't stop to think that beach parties were rare in Madison and that there were few prospects of me galvanizing teen beach-goers in some Frankie Avalon/Annette Funicello fantasy.

After many months we compromised on an acoustic/electric model, in case the beach option came up. He bought me a Gretsch Clipper hollow-body guitar and an Epiphone amp with the condition that I take lessons.

My friend Greg Wallace, who had a very shiny Japanese electric guitar with 3 pickups and about 30 switches on it immediately brought his camera and guitar over and we took pictures of ourselves posing heroically with our new guitar/swords.

Greg and I took lessons at a music store called Ward-Brodt. In those days music stores made most of their money selling band instruments. The store floor at Ward-Brodt was a sea of brass instruments, marching drums, and sheet music. But they were one of the first stores in Madison to sell a few electric guitars, and that's all they had: a few. They kept them in an alcove off to the side along with a stack of amps. All the amps and guitars were jammed in there, very concentrated. It was the the hot spot. Vox teardrop guitars, Hofner basses, Kustom amps with sparkly Naugahyde covers and some abomination called a "2x4" that was just a plank of red wood bristling with pickups and switches.

Lessons took place in the back storerooms, so while we were waiting Greg and I would surreptitiously crack the cases of new, unsold guitars. I remember being overwhelmed by the varnishy smell and sight of a Fender Coronado guitar in a plush red case. We opened the case and gasped. The power and the glory--it was a Wildwood model--made from the wood of trees injected with brown, green and orange dye as they grew. It looked like a guitar made from an oil slick. Fender only made them for a year or two.

Lessons took place in the back storerooms, so while we were waiting Greg and I would surreptitiously crack the cases of new, unsold guitars. I remember being overwhelmed by the varnishy smell and sight of a Fender Coronado guitar in a plush red case. We opened the case and gasped. The power and the glory--it was a Wildwood model--made from the wood of trees injected with brown, green and orange dye as they grew. It looked like a guitar made from an oil slick. Fender only made them for a year or two.

All the freaks and self-styled musical revolutionaries hung out or worked at Ward-Brodt. Adam Mickey was the electric guitar curator. He had a ponytail. He had an earring. We stared at his ponytail and earring. Later Adam moved to San Francisco and joined a band called Lamb and made an actual vinyl album that came out on an actual record label. His little brother showed it to me. Gasp. We all immediately started growing our hair out. (Grow, hair, grow.)

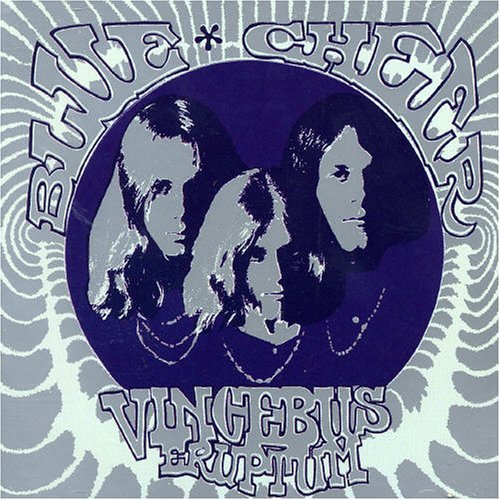

There was no rock music on TV. It was all Ray Coniff, Robert Goulet, Edie Gorme and  other crooning lounge lizards. When something with electric guitars was rumored to be on afternoon TV our school would partially empty out. Everybody went home to see Blue Cheer on the "Mike Douglas Show." (Who booked that?) We engaged in heavy parental negotiations to stay up late to see Jimi Hendrix on the Dick Cavett show, Janis Joplin on some other late-night show.

other crooning lounge lizards. When something with electric guitars was rumored to be on afternoon TV our school would partially empty out. Everybody went home to see Blue Cheer on the "Mike Douglas Show." (Who booked that?) We engaged in heavy parental negotiations to stay up late to see Jimi Hendrix on the Dick Cavett show, Janis Joplin on some other late-night show.

We patiently sat through Topo Gigio (the talking mouse-puppet) and the ever-present plate spinning guys on the Ed Sullivan Show to get to the rock band playing in front of a goofy backdrop (big birds for the Byrds, airplane models for the Jefferson Airplane, and so on).

Existentialism

Greg and I formed a band. I needed more gear. My mother had once won a set of books by asking a question of the "Great Books" column in the Capital Times. She wrote in and asked, "What is existentialism, anyway? Is it a fad?" They answered her question and put her picture in the paper, pointy glasses and all. Then they sent her about 25 books, Great Books; a series. Plato, Pascal, Socrates, and others.

Greg and I formed a band. I needed more gear. My mother had once won a set of books by asking a question of the "Great Books" column in the Capital Times. She wrote in and asked, "What is existentialism, anyway? Is it a fad?" They answered her question and put her picture in the paper, pointy glasses and all. Then they sent her about 25 books, Great Books; a series. Plato, Pascal, Socrates, and others.

I thought I could do that. I submitted a question to the "Tell Me Why" column and they bit. ("What do bees do in winter?") I won a set of encyclopedias (not very good ones), they came over and took my picture amidst the books, and put it in the paper with a short article. The very next week I made my mother take me and the encyclopedias down to the Buy/Sell shop where I swapped them for a fuzzbox. I still don't know what bees do in winter.

I spent the next two years growing my hair.

Greg and I found a drummer (Doug Ross) and practiced in our basement. We were very loud and had lots of people over. 20 kids in the basement. To this day, when I am home shoveling snow over the Christmas holidays, some elderly neighbor, also out shoveling snow will totter over and say, "How did your parents ever put up with that? Veblen Place just shook. It just shook." I asked my father about that and he said, "Well, we did know where you were." (Did they ever.)

I learned that if you had a guitar and played in a band it was quite OK to have an attitude problem. People expected it. That was handy. Later, in my twenties, I learned that if you were a composing guitar player people also expect you to be spiritual, or tortured, or spiritually tortured. Also handy.

Besides buying more and more gear, we invested heavily in psychedelic lighting (both Greg and I had income from paper routes). Black lights. Strobe lights. If we washed our white shirts in Tide and wore dark vests under black lights we appeared to be a bunch of glowing arms playing music. We were pretty sure playing under the right lighting might enhance some state of mind related to creative music-making.

Failing that we would put down our instruments and set the strobe light to flash every 1/2 second. If we jumped up and down in sync with the strobe it looked like everyone was levitating. This was great fun until the time Greg landed on the neck of my Gretsch hollow-body electric. Crack. Just as well. I got a red Gibson SG then, a real electric guitar. (No beach parties with that one.)

Our first great humiliation as a band was at the James Madison Memorial High School Rock Festival. This was in the wake of Woodstock and our set list reflected it. We played "Soul Sacrifice" by Santana, some Who songs, some Blind Faith, and (my moment) "I'm Going Home" by Ten Years After. It didn't go that well. The next day, sitting in homeroom, Mark Gongieu, who I thought was one of the cooler guys at school said, "You guys were great last night." Hopefully, I said, "Really?" He said, "No. You were terrible." He went into detail about why we were so terrible.

After that we wrote our own songs. We were inspired by the extended, side-long compositions bands were writing. Concept music. Rock operas. Different time signatures. Dynamics. We were inspired by Thick as a Brick (Jethro Tull) Tommy (The Who) and by our new-found interest in psychotropic drugs.

Drugs

Madison, being a college town and self-styled crucible of revolution had powerful, clean drugs and they found their way to the suburbs, or the suburbs would bike downtown to the revolution and find them there. We had a good gang composed of freaks, intellectuals, non-jock types, and budding musicians. We spent many magical evenings in each other's company, heads filled with LSD-25. I'm not sure how I'd feel or will feel about my kids taking mescaline or acid, but it was wonderful for us. A universe of color and sound opened up. Our minds engaged each other in ways that have kept us life-long friends. Intelligent company, a warm summer night, good music to see, bikes to ride, and clean blue microdot. We'd go downtown and wander the fringes of some block party or riot or both, get tear-gassed, bike back to our homes, pretend to go to bed, sneak out, meet somewhere, and walk all night. We'd look for Mescalito. One person would take the Don Juan role and the other would play Carlos Castaneda.

Guitar Players

There was a lot of music coming through Madison and a lot of bands in Madison. More than the big guns (Hendrix, Clapton, and Jimmy Page) I think I was more warped by what I could actually see in town. Gary Geisler, Mark Hambrecht, and Jim Pharo were my age and my competition and I stole from them. Further up the ladder were the traveling bands that came from Chicago and Milwaukee: Short Stuff, The Siegal-Schwall Band (Jim Schwall with his DeArmond pickup taped to an acoustic guitar) and especially Harvey Mandel. Soup was a band from Appleton with an amazing guitar player (Doug Yankus). Bob Schmidke was Madison guitarist who played in the band Tayles.

St. Paul

I left Madison to go to Macalester College in St. Paul. Starting college life in 1972 was like showing up at a party at 2:30 AM. The revolution was over.

Steve & Grandpa's Gibson

Before I left my father gave me his twelve-string Martin and my Grandpa's guitar, a 1912 Gibson. The Gibson is the guitar I'm holding on the back cover of Yr.

When my dad gave it to me I took it out of the case and did some high hammer-ons ala Harvey Mandel. He said, "That's probably the first time that guitar has been played above the third fret."

I played lots of acoustic guitar in my dorm room. Towards the end of my junior year a guy named Scott Stevens told me he had a two-track tape recorder that had overdubbing capabilities, a "Howard" reel-to-reel. He lent it to me for a long weekend. I barricaded myself in my room and, sleepless, overdubbed everything that made a sound in my room. The water coming out of the tap. My keys. Clapping. Playing my desk. Many guitars. At the end of a few days I had a nice little piece of sound sculpture and a flat hairdo from wearing vise-like Koss headphones around the clock. Karen Pernokas knocked on my door, distraught over her finals and moving plans. I asked her if she wanted to listen to what I had recorded. She settled down on the floor with the headphones on, I spooled the tape onto the machine, played it for her, and waited anxiously. When it was over she got up, took the headphones off and said, "That was just what I needed." My first review. I was thrilled. I thought "Maybe I can do something with this."

First Album

In my senior year the music department put in a small electronic music studio. It had a four-track Dokoder, an EML 101 synthesizer, one battered microphone, and a tiny mixer. The studio was put in the only space available; a large closet where the Macalester pipers would store their kilts and bagpipes. (Macalester has a Scottish sort of theme). Even though the electronic music studio smelled like sweaty kilts it was heaven to me. I finished up my fine arts major and spent the last year in that studio. That's where I recorded my first album.

In my senior year the music department put in a small electronic music studio. It had a four-track Dokoder, an EML 101 synthesizer, one battered microphone, and a tiny mixer. The studio was put in the only space available; a large closet where the Macalester pipers would store their kilts and bagpipes. (Macalester has a Scottish sort of theme). Even though the electronic music studio smelled like sweaty kilts it was heaven to me. I finished up my fine arts major and spent the last year in that studio. That's where I recorded my first album.

Studio

I worked as a board operator on the overnight shift at Minnesota Public Radio for about five years. My job was simply to tend the station in downtown St. Paul, since all the programming came from Collegeville. I listened to a lot of classical music during the night.

I would eat my bag lunch at 2AM, up in the newsroom with whomever was around. Bill Tilton was a frequent MPR night owl. Bill had spent some time in jail for burning up Minnesota draft records.

In jail Bill studied law, and on his release became the only convicted felon to pass the bar exam in Minnesota. He worked for legal aid, made public-interest programs for MPR, and made frequent forays to Africa. He told me that being in jail with nothing to do inspired him to now forgo sleep, work at night, and travel everywhere. He showed me photographs of Africa (I used one of them for the cover of "Safe Journey"). He sent me postcards from strange places. I determined that I would go stranger places and send him postcards in return.

I set up a studio in a warehouse space with a Tascam 8-track tape recorder, a small mixer, and three mics. I didn't have a reverb unit, so I ran mics and speakers across the hall to an abandoned sculpture studio. That was my reverb chamber for Yr, my second album, which I put out myself after collecting about 200 rejection letters. Reviews praised the "organic" sound, but it was just the sound of ignorance and lack of gear. The time I spent in that studio taught me how to get a lot of the sound I was looking for from just an instrument and a microphone.

Yr was sort of a hit. It got a lot of great reviews. I sold some. I got to know my local UPS man well. I made some money. ("Maybe I can make a living at this!") I was always shipping boxes of vinyl around, many of them to New Music Distribution Service in New York. Carla Bley and Mike Mantler started the company when they found it hard to get records on their label (Jazz Composer's Orchestra-JCOA) into shops. I believe that early on, NMDS/JCOA was the only company who would take the fledgling ECM label for distribution in the USA.

Norway

I got a letter from Rich Frank, the music director at a college radio station in California who suggested I send copies of Yr to Ricky Schultz at Warner Brothers and ECM Records in Munich. Sure. Why not? Ricky called soon after I sent him the LP and said he was on his way to Munich to meet with the ECM staff. At that time ECM was distributed by Warner's in the states. He said he'd "buttonhole" Manfred Eicher, and suggest we do an album together. (Fat chance.)

Ricky took my record and press kit over. My press kit, at that time, was a William S. Burroughs type cut-up of all the rejection slips I'd received.

The ECM staff had a good laugh at my press kit, and Steve Lake (from ECM) sent me a letter duplicating some of the typewriter strikeovers from my rejection letter cut-up. He said no, they would not be interested in putting out my album, but making a record with them would be a possibility.

A few months later Marc Anderson and I found ourselves, to our great surprise, on an flight from Minneapolis to Oslo, Norway. The plan was to record an album in three days with Manfred Eicher and mix it on the fourth. This is how ECM did things. It was alternatively grueling and inspiring. This was a new way of working for me.

I was already a big fan of the label. At our meals out I would press Manfred for details on all the recordings and musicians I was already so familiar with, but familiar with as a fan. I couldn't believe it was happening, that I was in such exalted company and would be part of the label.

When we finished mixing Manfred called up Jan Garbarek, who lived in Oslo, to come over to listen to the final product. We listened. I didn’t like it. Marc's two congas had gone flat from a major 2nd to a minor 3rd for the final 21 minute song, and the resulting minor second against the tonic made it impossible for me to bring in the tape loops I had planned for that piece. Manfred said, "It's enough, it's beautiful already, more loops would be too much." I was in a foul mood, and at the conclusion of the playback I stalked out of the control room in a huff to pack up my gear in the studio. Jan followed me out and said in his Norwegian accent, "I think it's good, I think it's a good album." I said, "Doesn't Manfred just drive you crazy sometimes? Don't you ever want to run out screaming into the streets of Oslo?" He nodded and said, "Yes, yes, yes. I do not think it would be a good record if you did not feel that way."

I like the album now.

Wax

From 1979 to about 1985 I worked in a record store in Minneapolis called "The Wax Museum." I learned a lot about music and the music business from working retail. Those years were a fertile time for music in Minneapolis. There were lots of bands breaking out. Working in a store made it possible to go see lots of shows for free. Lots of metal and punk-rock, which I never would have liked unless I had to hear it over, and over and over and over. Joy Division, Roxy Music, Brian Eno and his productions, Stiff records, Pere Ubu, The Replacements, pre-famous Talking Heads and U2. Once night after work we all went to see U2 play a club in Minneapolis. The band was barely out of nappies. We'd go see Prince in clubs. At the record store we were the first to hear about his secret club shows. The pulse of the cities.

Nepal

In 1985 I applied for a grant from the Minnesota Composer's Forum. A very nice lady from the MCF called me up at home and said, "You got your grant." I thought I had won the lottery. My girlfriend asked, "How much is it for?" I didn't know. I called back the nice lady and asked. She laughed and said, "Six thousand dollars." A tidy sum.

My grant proposal was to go travel somewhere, record sounds, and use the pitch or event quality of the sound to spark the composition process. Because I had been teaching a recording class at the Naropa Institute in Boulder I knew the school was starting up a study-abroad program. The first trip would be to Nepal, and I signed on as quasi-faculty though I never really did anything in that capacity.

Going to Nepal was as good as LSD had been in terms of brain-stretching, and the experience of difficult travel in strange countries changed how I approached many things, including working with my mind. I learned that it was a good thing to go far far away for as long a time as possible. It was good to leave mental baggage at home and to turn one's world completely upside down. It was good for me to leave my guitars at home and let the calluses fall off of my fingers. It was good to get away from the phone, friends, lovers, familiar food, familiar smells, and familiar ways of thinking.

It was also good to travel and record sounds to use in sparking the creative process. "Three Letters" from the album "Big Map Idea" is from that first trip to Asia.

Asia

From 1985-97 I traveled all over Asia. I worked for the Naropa Institute and I got a few grants. It was exhilarating to study Balinese drumming in Bali and to hear endless Javanese gong cycles in Java. Sounds were much different far away from my studio and guitars. My passport ran out of spaces for visas. I had more pages put in, and then I filled those up. At my Minneapolis apartment I had a square, cardboard grocery box from Country Store where I stored my travel items, always ready to go away again. "I'll be gone for the autumn," I'd say to Marc. "You're always gone," he'd reply.

Bill Tilton got lots of postcards from exotic locales. I liked Asia; the food, the vibe, the long steamy days, and the endless possibilities for strange travel. It was easy to travel with next to nothing. Endless travel under trying circumstances. A friend of mine said, after his difficult trip in Spiti, "I just learned to be comfortable with being uncomfortable and that solved everything."

Questions

In 1993 Brian Eno came through the Twin Cities doing an interview tour. He was promoting his album with John Cale ("Wrong Way Up"). His interviews on this tour took place in front of an audience, and he asked to be interviewed by local art/musician types. Chuck Helm, director of the Walker Art Center, asked me to be involved. In advance of the interview Brian sent out a 6-page letter titled "To the person who is interviewing me." It listed a lot of questions that he'd rather not be asked, which I thought was incredibly arrogant until I read the letter. He had found that, having done hundreds of interviews over the years, many of the familiar questions he was asked led nowhere, and he was rarely asked things that really interested him. For instance, he was often asked about some sound on some album that he had long since forgotten about. "What was the buzzing sound 20 seconds into cut three of 'Another Green World?'" "What's David Bowie like?" He suggested that the interviewer ask him about other things that interested him like, for instance, perfume.

I thought about all the familiar questions I'd been asked over the years.

1. Where do you get your ideas?

Besides just getting ideas from mucking around on guitar I get inspiration by setting up chaotic events in the studio and picking the best bits. I'll play a certain line on guitar or keyboard, have the guitar or keyboard create midi events, record them to a sequencer, then have the midi events play different samples tuned in unisons or diatonic scales. Then I'll have other musicians come in and play to those parts. Eventually I have something good, and I overdub instruments over that.

Another approach is to record a solo guitar line or drum track and play different instruments to that track. On Monday I'll work out a 12-string line in the key of E. Not listening to Monday's work on Tuesday, I'll play a mandolin line in the key of A to the same basic drum or vocal track. By Friday I'll have five tracks filled up and I'll finally listen to them all together and keep what works. It's not like sitting down in a bare white room with a quill pen and manuscript paper. I wish I could do that, but that's just not a tool in my toolbox.

A friend of mine, Homer Lambrect, told me about a summer when he'd decided to do a month of composing. He set things up so he had all his paperwork done, the house to himself, and nothing to do except hold a pen and stare at music paper. The time came. He waited, pen poised over the paper. Nothing happened. Nothing happened for a week. He finally decided to give up and refinish his bathroom. That's when things happened for him. He was flooded with ideas while working with his hands.

I think traveling a long way from home or doing non-music things with your body will have the same result. It's good to put the music tools down and do something that will erase or engage your mind. Go away, remove all the supports that tell you how and why you are. It's amazing to me that guitar and gear-oriented magazines place such an emphasis on gear and guitars and so little emphasis on creativity. What do people do to free up their minds to be creative? How can you use the tendencies and forces in your mind in the service of creativity?

2. How would you describe your music?

It's too bad that the words "fusion" and "progressive rock" have such horrible connotations. How about "post-modern neo-primitivism?" (That’s Willie Murphy’s suggestion.)

3. What kind of gear do you use?

I have a friend who is a good amateur photographer. She told me that when she shows someone a particularly good photograph she's taken the response will often be "That's nice. That's really good. What kind of camera do you have?"

Whenever musicians I meet get all wound up about whatever they do or don't have in their studio I point out that most home studios have more and better equipment than the Beatles had for "Revolver." Whenever guitarists get all wound up about whatever guitar or device they do or don't have I point them to Jimi Hendrix's solo in "Machine Gun" from the Band of Gypsys album. He had a guitar, a few amps, a fuzzbox, Univibe pedal and wah-wah, and he played the solo on that record in one take. The only guitar solo that approaches those heights is his “Star Spangled Banner” solo from Woodstock.

4. How do you get that electric guitar sound?

When the pickups of my Stratocaster are close to the speaker there's some sort of magnetic interference that takes place between the speaker coils and the coils in the pickups. They fight. It creates a ripping, tearing sound. When I took my amp in to have it fixed once the tech called me up to tell me that the transformer in the amp was bent and the metal leaves were separating. He asked me if the amp had ever been dropped. I remembered that when we had inebriated help loading out after a gig in Winnepeg some guy dropped my amp 5 feet off of a loading dock.

That's how I get my electric guitar sound. If there's ever a Steve Tibbetts Signature Marshall Amp, there will have to be an inebriated guy at the end of the assembly line who drops each Steve Signature Model about five feet on to a concrete floor.

5. What are your main influences?

Marcus Wise called me up one day and said, "You should come hear Zakir Hussain play this concert that's happening in town. He's playing with Allah Rakah, his dad." I went in order to see Zakir and his father play dueling tablas. With them was Sultan Kahn, playing a Sarangi, a bowed Indian instrument fretted with the back of the fingers. I had never heard so much color from an instrument in my life. I was stunned. I thought later that perhaps I had just been caught by surprise by something new. Days later Marcus gave me a tape of the concert, and it was the music, not the surprise. I listened to his playing over and over and tried to imitate the singing, voice-like quality of the Sarangi. The frets ground down on my 12-string and sounded more and more like what I had seen and heard. The frets are nearly flat now. I took it to Hoffman Guitars to have it re-fretted. I handed it to Ron Tracy, their luthier, and Ron said, "Do you like the sound?" I said, "I love the sound." Ron handed the guitar back to me and said, "Then I'm not going to fix it for you."

Here is a selection from Marcus' recording of Sultan Khan that night.

Synthesesia

When I was in third grade I needed eye surgery. My right eye would often turn towards my nose and stay there. This was disconcerting to my parents. I wore a patch on my glasses. My ophthalmologist said I had a "lazy eye." I felt bad about my lazy eye.

My ophthalmologist operated on the muscles of my eyes. After surgery I had to stay in a dark room with patches and bandages over my eyes for a week. There was no light at all. My parents came in and read to me every day, for hours on end. They read "The Five Children" by E. Nesbitt and selections from "Just So Stories" by Rudyard Kipling over and over, at my request. My brain, having no visual input, made a startlingly clear set of visual images to go with the words in Kipling's book. "The Butterfly That Stamped" was huge, glowing, and iridescent. "The Cat That Walked Alone" was two stories high and made of rainbow-hued metal.

When my parents left the hospital the images stayed. They stayed with me through the night, in dreams. When I would wake up I would not be sure I was awake. There was total darkness, and the dream animals still there, right in front of me.

Years later, when I had my own studio and was able to spend a lot of time mixing the music I had recorded I noticed that my mind would always settle on some imagery to go with the music. Sometimes I would follow the imagery, and let it help direct the music. Later, I noticed this sort of thing happened all the time, not just in the mixing stage. Make a sound, see a form. Other artists have told me it happens to them as well. Draw a line, hear a sound.

I had forgotten about the metal cat and the luminous butterfly until I came home from the studio one May evening, this year. My children were asleep and my wife was previewing stories on tape for the kids. She said, "Listen to this." It was Jack Nicholson reading "The Butterfly That Stamped." Think of it--Jack Nicholson's voice, all oily, soothing, menace saying, "Once upon a time..." I listened for awhile and remembered everything.