Å–Rykodisc / Hannibal Bio

In 1976 I had a job in a record store in St. Paul, Cheapo Records. One of my co-workers was a guy named Morrey Nellis. Morrey became director of intramural athletics at Macalester College where I used to go for a run every now and then. In 1990 or '91 he gave me a cassette of hardingfele music saying, "Listen to this." He got it from his wife who was director of the Hardingfele Society of America.

A hardingfele is a Norwegian fiddle that has sympathetic (drone) strings under the fingerboard. It has a rich and resonant tone. A huge sound. They are beautiful instruments, decorated with pearl inlay, rosette patterns and other sorts of filigrees. Besides having a beautiful sound, the hardingfele (or "hardangar fiddle") has a lore and mythology all its own. The fiddlers and their instruments were sometimes thought to be in league with certain spirits, or even Satan himself (or Satan herself).

It was thought that, in order to play his (or her) best, a fiddler must make a pilgrimage on a moonlit night to certain waterfalls and throw in a leg of mutton to invite the spirit of the waterfall to reveal itself. The spirit ("fossegrim") would break the fingers of the fiddler's left hand so he or she could reach formerly impossible fingerings, and then break the fingers of the fiddler's right hand so the bow could be held more efficiently. The fiddler would then be beholden to the spirit and begin a career of roaming the countryside and playing. A good fiddler was said to be able to play in such a way that a glass of whiskey would dance across a table and up the fiddler's arm. The Lutheran church took a dim view of these legends and encouraged mass smashings and burnings of these instruments.

I took the cassette that Morrey gave me back to my studio and, after it started, had to sit down and listen to it. It was good. The cassette had little in the way of information. It was all in Norwegian. I did figure out that the fiddler was a man named Vidar Lande.

In' 93 or'94 I went to a concert by the Finnish band "Vartinna." I bought a CD at the show and Phillip Page, the guy selling me the CD looked at my check and recognized my name from my ECM releases. He said he had a record shop in Helsinki. I asked him if he knew where I could find Vidar, and he said he would try to hunt down his address. About two months later he sent it to me. I took two tunes I liked from Vidar's cassette, dubbed them to my 16-track, and added a few tracks of guitar and gongs. Then I sent a tape off to Vidar and asked him if he'd like to do an album together. He wrote back and said he would.

This was about the time Chö (my album with the Tibetan singer Chöying Drolma) was coming out. I was looking forward to doing a project that seemed a little more simple that Chö. The project with the Tibetan nuns was complex. There was a lot of travel involved, and a great deal of conflict with structures of power, both institutional and personal. Norway seemed simpler. Norwegians in Minnesota seem more up-front about things. In Asia it's hard to figure out what people really want, and what the real story behind a situation is. As it turned out, there was just as much mysticism and intrigue in Norway as there was in Nepal.

At that time I was preparing to travel to Bali to administer a study-abroad program, and just before I left Vidar wrote and said he couldn't do the project. He said he hadn't been playing music much and had been busy with his duties teaching Kierkegaard's philosophy at Oslo University. However, he did recommend a player from Folkedal named Knut Hamre. He said Knut had great tone and was easy to work with.

I sent a letter to Knut, and he replied favorably to me at my study-abroad address in Ubud, in Bali. I had brought a cassette copy of his CD to Indonesia, and listened to it a lot. The cyclical nature of the hardangar fiddle music seemed to mesh nicely with the gong cycles of Javanese and Balinese music.

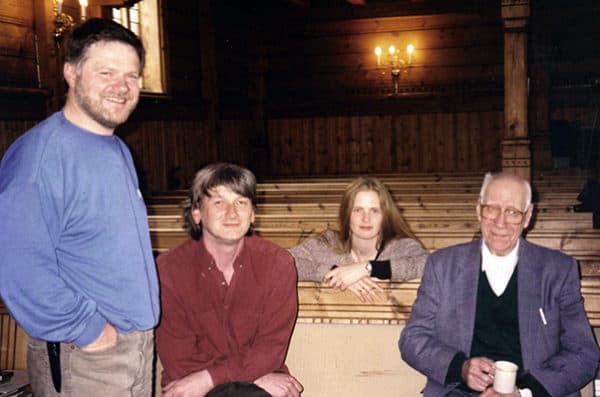

After I returned, Marc Anderson and I flew to Oslo and caught the train to the western side of the country. We spent about 10 days recording with Knut and Turid in a small church in Utne. Every morning we would board a ferry to cross the fjord from Granvin to Utne. We would run through the tunes together and work on arrangements, then Turid and Knut would play while we recorded them.

The recording project in Norway was fairly straightforward. Knut plays about eight to ten hours a day, so this type of recording session was easy for him. There were moments when his instrument was warmed up, the room felt right, and he would say, "The song is coming now." And it would.

The distant sounds of the ferry or fishing boats ("fiske boats") sometimes crept into the recordings. Knut's wife Aud would pack a lunch of lefse, coffee, and goat cheese for us. At the end of the day we'd get the ferry back home. On the ferry, or drinking cider waiting for the ferry, we'd talk about the lore that swirled around the instrument, its players, and the subjects of the songs. A lot of the songs are about Huldres, mythical mountain beauties who come and sing songs to fiddlers who have fallen asleep under trees. "Underground people," Turid called them.

There isn't much that happens in that part of the country, so our recording project attracted the attention of the national television and ratio stations. A crew came to interview us at the end of a long day of recording. They asked us if we thought the CD would sell. We surprised them by saying, "No." Hardingfele music is not all that popular in Norway, and I could tell that the album would be exploring the stranger side of the instrument. On the ferry home Knut mentioned an old Norwegian saying, something like, "The only exercise my father got was leaping across the room to shut off the radio when hardingfele music came on."

After the end of the television interview in Utne Church Knut said, "I remember a song, a song is coming." He unpacked his fiddle, we set the microphones back up, and everybody sat down and listened while we recorded him playing "Huldreslått." Turid leaned over and whispered that Knut was playing a song about a huldre. Marc said, “What are huldres?” Turid whispered again, “Underground people.” Knut seemed to invoke something. Huldres, maybe. The atmosphere was surreal. The grain in the church's wooden walls started to crawl.

Marc wrote these notes in his position as scribe: "...with everyone around, T.V., radio museum. Fiske boats and evening traffic throbbing about. We sat in rapt attention. Chocolate and caffeine hardly noticeable this late in the day. Underground people."

Recording notes: I didn't like the sound of the DAT I used to record the nuns in Nepal, so I brought an analog Nagra reel-to-reel tape deck. I used two Neumann U-87s with the Nagra.

I was looking for advice on microphones from a friend and he said, "I never heard a good recording of a violin that didn't have a lot of the room in the sound." I found that to be true with the hardangfele. I put one microphone close to Knut, and one about 20 feet away in the church. This worked well, so we used the same approach with Marc's drums and my guitars. We used very little EQ or reverb in the mix, and kept the recording chain analog all the way to the end. I'm not an analog purist, but the medium seemed to suit the music.

I did a lot of gong sampling in Bali. The school I worked for there has a Balinese Gamelan orchestra, and when time permitted I would drag each instrument into my room and work late into the night to get good stereo samples of it. My room was right on a rice paddy, and I did most of my sampling at night, so that's why you can hear insect sounds in some of the samples. It wasn't my intention to be overly pastoral, though the bugs twittering and frogs croaking seems to fit in some places.

.jpg)