MyECM

I curated a playlist for ECM as part of their venture into the world of streaming (an article from Pitchfork is here).

My annotations for the playlist are below, and a more concise version is on ECM's website here. The playlist is now up at Tidal and Spotify.

I curated selections from (mostly) the first 200 releases that dovetailed with my beginning at the label and from my interactions with ECM’s artists and employees.

If the tone of the writing is adorably naïve, well, Minnesota is a provincial place. When Charles Lloyd comes through town we all turn out and try to meet the musicians in the band and get our CDs autographed, Sharpies in hand. I remain a fan of the label, I do occasional recordings for the company, and in the process I sometimes get to encounter ECM’s musicians and employees as fellow travelers.

Here's what I wrote to go with the playlist.

My ECM: STibbetts

(From “Horizons Touched: The Music of ECM”) Many call, but few are chosen. Wisconsin-born and Minnesota-based guitarist Steve Tibbetts is one of three musicians who arrived at ECM by the time-honored route of sending material to the label. A copy of his privately pressed album Yr attracted attention in 1980 and led to an invitation to record, and Tibbetts and percussionist Marc Anderson left US soil for the first time and headed for Oslo.

At different times, Tibbetts’s music has appeared to be close to diverse idioms and sub-genres, from minimal and ambient music to world folklore and alternate rock. But, like so many of the label’s veterans, he goes his own way.

-Steve Lake

Prologue: Downtown St. Paul, 1976 A 21-year old man with a red ponytail shuffles aimlessly down the icy sidewalk on a bleak December afternoon. It’s his lunch break from his temporary job at Minnesota Public Radio, and rather than eat his lunch in the grim MPR dining room he decides to wander the winter streets of St. Paul. Passing a record shop, something in the window catches his eye. He hesitates, hands deep in his pockets, then turns, doubles back and walks through the door.

Act 1: The Purchase

“If the music sounds like the cover looks…” I said, hesitantly, purchasing After the Rain at Three Acre Woods record store in downtown St. Paul. “It does," replied the sullen record clerk.

Thus began my life as an ECM devotee. Six years later I found myself in Oslo, Norway, eating a goat cheese sandwich across from Manfred Eicher, founder of the label, during our breaks from recording Northern Song. I wanted to talk about the stories behind the ECM catalog. I peppered him with questions. Why were there two different back covers to Bill Connors’ first album? “You noticed that?” said Manfred, incredulously. (I’d already worn out one copy of the album and given two away). I asked him about the Talent Studio recording of Egberto Gismonti’s first album Dança Das Cabeças. Manfred said, “Yes, getting off the airplane Nana and Egberto said, ‘It’s too cold here in Oslo to play, too cold, too cold!” Manfred rubbed his hands together. “Too cold! But the next day we went to the studio and started recording. We recorded and mixed the album in two days. Incredible. Incredible.”

I found rabid followers of the label everywhere in my travels. In 1983 an executive at Warner’s took the bill for our coffee, looked at the green slip of paper, and said, “Red Lanta.” I said, “What?” He said, “The bill is for $10.38. That’s the catalog number for Red Lanta by Art Lande. ECM 1038. Do you know the album?” Fans of the label make a mission of apprising other fans of hidden gems in the catalog. In 1986 I gave Leo Kottke a copy of Ralph Towner’s Solo Concert. In 1987 I put a copy of Leo Kottke’s album Guitar Music in Manfred Eicher's hands.

The label and the people who work there shaped my aesthetic in many ways: high production values, detailed recording, and a marketing sensibility shaped by intelligence and dignity. Of course, you can’t talk about the aesthetic of the label without talking about Manfred Eicher, so I won’t, except to say anyone who’s worked in any capacity with the label knows these three thoughts all too well: 1. Manfred will really like this thing. 2. Manfred will not like this thing. 3. Why should I care if Manfred likes this or not?

2017: M. Eicher receives a new Killerspin 800 ping-pong paddle

Jarrett vs Eicher, 1991

Thus, my musical consciousness has been slowly warped over the years by the label’s artists, its founder, and its employees.

Playlist Annotations

Connors In college I looked for work in the music industry, anything, anywhere. I picked up a temporary job working as a security guard for Schon Productions, $20 a concert. I was working for Schon at the St. Paul Civic Center one afternoon in 1974 preparing for a Steve Miller concert when Return to Forever (the warm-up act) loaded in. Return to Forever was touring their new album, Hymn of the Seventh Galaxy. Bill Connors played guitar, a black Les Paul. He was very good. When the sound check finished a friend of mine walked over and said helpfully, “Your mouth was open while they were playing.” I closed it and said, “Well, you know, the guitar player.”

I bought Bill Connors’ album Theme to the Gaurdian (yes, mis-spelled, probably not on purpose) and listened to it every morning, every day. Years later I put on the album for a friend while cleaning up the studio after a long day’s work and she said, “Wow Steve, sounds like you.” No, in fact I sound like Bill Connors—his left-hand vibrato, his sense of space, his liquid phrasing, the way he lingers on a note.

One of the first conversations I had with Manfred concerned that album.. He put his coffee down, paused dramatically and said, “Ultimate acoustic guitar album.”

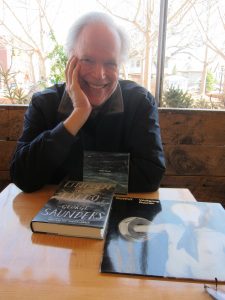

Towner At lunch a few months ago the 12-string guitarist Leo Kottke allowed me to photograph a still-life I created consisting of Leo and items I had on hand: a copy of the book I’d brought as a gift, a very early ECM cover misstep (Output), and a copy of Ralph Towner’s newest CD. Leo already had the book ("Lincoln in the Bardo"); he took the CD with him.

Garbarek At the conclusion of recording Northern Song in Oslo, Norway, Manfred phoned Jan Garbarek (Jan lives in Oslo) and told him he might want to come over and listen to the finished mix. He came. We all listened, sitting in a row behind Jan Erik Kongshaug, the Talent Studio recording engineer. At the conclusion of the playback I stomped out into the studio and began packing up. I was a little disappointed. I was closing my guitar case when Jan came out and said, “I think it is a good record.” I stood up and complained. He listened and nodded slowly. He waited for me to finish, thought for a moment, and said in his deep voice, “I do not think it would be a good record if you did not feel this way.” Jan came back to the studio two years later to listen to the playback of Safe Journey and said, “Now you have two.”

Abercrombie About 10 years ago I went to see John play with Charles Lloyd at the old location of the Dakota Jazz club. In those days the club was located in an out-of-the-way mall located in an industrial wasteland midway between the cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul. It was a strange place at night, utterly deserted except for the club and an expansive model train exhibit. I introduced myself to John at the band’s break and he said, “First question…ummm….where am I?”

Codona When my first recording date with ECM was confirmed for Oslo in 1981 I biked right over to Northern Lights Music on University Avenue in St. Paul and bought the two newest ECM releases: Codona II and Meredith Monk’s Dolmen Music. The two albums stayed on the turntable at home. My girlfriend Barb said, “Can we listen to something else?” I said, “I’m gonna be on the label!” She said, “Yes, that’s good, congratulations, very nice. Can we listen to something else?”

Monk In February of 2017 Meredith gave a concert and workshop at my daughter’s college just south of the Twin Cities. We met Meredith backstage, and I arranged to drive her the next day from her hotel in Minneapolis to the Walker Art Center. She would spend the afternoon being squired around the Merce Cunningham exhibit by museum director Philip Bither. We took the long way to the Walker, talking so intently that I drove off Groveland Terrace and smashed into an orange traffic cone. At one point she said, “So, did you ever meet Colin or Nana? Don?” I said, “No, never, I wish I had.” She paused. She said, “That was really something. What a time.” Pause.

Berger Marc Anderson and I flew from Minnesota to Norway in 1981 for our first recording with ECM. Anybody’s first trip out of their country is going to be dreamlike, but this was doubly surreal to us due to the fact that flying from Minnesota to Norway is like traveling for 9 hours and ending up exactly where you started from. In the fun-house mirror version of Minnesota we traveled to, the sun rose at 10 and went down at 3 and the shadows on the snow were miles long and there were paintings by Edvard Munch in the hotel lobby, halls, and rooms. When we arrived at Talent Studios Manfred was already there working with Bengt Berger. Bengt had completed his album “Bitter Funeral Beer” the day before. Bengt greeted us and said, “We just have one more edit to do for the album. Will that be possible?” Well, sure, yes, of course. He was very kind, very gracious. Besides being good music, Bitter Funeral Beer was the thing that ended just before we started, so it has become a reference point of nostalgia. (Seek this album out.)

Saluzzi Manfred called from his office and said, “Come here, listen. Listen to this.” I went in, sat down, and we listened to a test pressing of “Kultrum.” It’s rare to sit and just listen to music, rarer still to sit and listen to an entire album with its producer. Years later I went to see Dino play at the Fine Line Music Café in Minneapolis when he was on tour with Al Di Meola. I introduced myself by handing him a copy of my most recent album, a Sharpie, and a CD of “Kultrum” for him to sign. Dino didn’t speak much English. He smiled, put both his hands over his heart, and bowed slightly.