Life Of–Press page

Some Biographical Material

Big Influences

Dave Ray was a big influence, not so much because of his legendary guitar chops or his storied career in music, but because he kept the rent on my studio low. Dave Ray was my landlord. He died in 2002. A street close to my studio has been renamed Dave Ray Avenue. I think St. Paul itself should be renamed "Dave Ray."

Because Dave kept my rent low I could waste time with impunity.

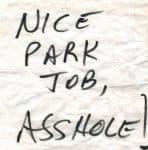

Once I pulled up to my studio in a hurry and parked at an obtuse angle and Dave, who was parked next to me, left this note on my dashboard before he pulled out of the parking lot. It was my girlfriend’s car, so he didn’t know it was my "park job."

Chuck Brown, my CPA, was also a big influence. Chuck taught me how to manage my money so I could work part time. That way I could spend hours waiting for musical plots to reveal themselves (see “musical plots,” below).

Pete Seeger was a big influence because of a record he made called “The Folksinger’s Guitar Guide.” His voice was soothing, like Mr. Rogers’ voice. He was my vinyl companion. I played the record over and over and practiced along. Vinyl Pete was very patient. Pete would help you get tuned up and show you something called the “church lick.” Once my dad shouted from the kitchen, “Can you play something else please?”

Then my dad brought home a Kingston Trio album and I let go of Pete Seeger and gave myself over to the almighty E minor chord that starts “Greenback Dollar.”

We had the uncensored version in our Madison house, making us untamed, wild, and free, in our own suburban way. Radio played the censored version.

After some time the focus turned to album photos: the front cover of “Electric Warrior,” the back cover of “Johnny Winter And Live.” I didn’t listen to the music on those albums that much. I just wanted to be one of those guys. I wanted to have an album on the front racks Victor Music in the Hilldale mall that had a cover as cool as Electric Warrior.

Wobblies

My dad worked for the University of Wisconsin School for Workers. He drove around the state teaching labor law. When he’d break out his 12-string at a meeting of fatigued Boot and Shoe Union workers in Steven’s Point everyone would perk up. Guitar is an attention-getting device. Everyone would sing from the Joe Hill songbook, or whatever passed for an AFL songbook. (My dad considered himself an IWW guy, not exactly a Wobbly, definitely not a CIO man. He said, “It was a sad day in 1955 when the AFL hyphenated itself to the CIO.”)

My dad helped organizers and union workers network by inviting them over to our house. 20 people would come over, eat, and then break out an assortment of instruments: guitars, banjos, flutes, recorders, autoharps, psalteries. Everyone smoked. I could stand up slowly and move through gradated layers of smoke.

Some Background

Walking and Assembling Sound

In 2013 I met a French clown in a café in Lhasa. I was in a restaurant called “Tashi 2” when I heard a voice switching effortlessly between French, English, and Tibetan. Marion was a juggler, translator, and one of three westerners with a permit to live in Lhasa. She’d already summited Everest, the trip financed by a French bank (Milestone Capital). The bank wanted a photo of its logo at the highest point in the world.

In 2014 Marion and I and a small group took a bus from Kathmandu to Lambagar and walked north to Lapchi, over very challenging terrain. After a hard day trekking I asked Namgyal, our guide, if we would ever hike high enough to leave the leeches behind. He said, “Yes, tomorrow. Tomorrow we go higher and leave the black leeches behind.” He paused. “But then we walk through the yellow leech area, higher up. They drop from the trees.”

Marion chimed in, “Yes, sorry, monsoon is not the best season for this, but it was the only time we all had free.”

After arriving in Lapchi my more energetic traveling companions took a day to climb to remote retreat caves. I spent that day wandering around the lower part of the mountain. I’d brought recordings of loops and beds of sound, thinking that if I walked in the spectacular landscape and listened without much agenda that sounds could be encouraged to assemble themselves.

When I played around with the music back in St. Paul the images returned: here is a crevasse in Lapchi, here is a stupa.

We walked back to Lambagar and then east, to Bedung. We bivouacked in the village of Na. From there we made two higher camps and failed to make a technical ascent of Mt. Ramdung.

Inbred Process: Working Alone and Titles

Back in Minnesota I'd sometimes go to a local coffee shop with my laptop, headphones, and rough mixes to work. I’d edit with the coffee shop’s patrons in view. I’d assemble sound prodded vaguely by what I saw and heard.

Some of the titles to the songs and pieces of sound were from overheard conversations. They were just placeholder names, bookmarks, Post-it® notes. Over time, the placeholder titles gained some traction and acquired a ghostly sort of existence. They grew into significant little song-music-people. They began to exert influence over musical direction. Back in the studio, it seemed perfectly sane to ask, “Is it right that the song-person Emily should have a lacey high piano gong cycle in this section? Is it ‘right?’ Is it Emily?”

Transplant and Titles

Rewind to 2009. I gave my sister an immune system transplant. That story is here

My sister signed up for a clinical trial at MD Anderson Medical Center in Houston, Texas. My blood type, along with its complicated antigenic makeup was a good match. They killed her immune system with chemotherapy, pumped me up with Neupogen, whirled my blood and transplanted Steve into Ellen.

My immune system killed her late-stage ovarian cancer.

That narrative ends with my sister, having successfully integrating my immune system, arising as “The Creature Ell-Steve” (my sister Dorothy’s appellation). After I got home I titled a song “The Creature Ell-Steve.”

Recording Process

I don’t use much EQ or compression. The trade-off: the music can sound a little dull, like the speakers are wrapped in muslin. I tried jacking up the treble, like everyone seems to do, and it just sounded screechy and annoying.

There are two microphones in my studio left set up for acoustic guitar, a Mojave and a Neuman They haven’t moved in years. Using an un-matched pair seemed like the right thing to do. The Mojave worked well at the 12-string’s bridge, the Neuman made a home looking at the 12th fret.

I always call up Willie Murphy when I don’t know how to make things work in the studio. We usually end up talking for an hour or so, typically about the music business or Dave Ray, and when I hang up I realize I forgot what I called him for.

Guitar: Martin D-12-20

I have a Martin 12-string that my father gave to me. I came home from college for some winter break around 1978 and saw the guitar in its case, propped up against the shoe rack in the front hall of our house. I stamped the snow off my boots and said, gesturing to the guitar case, “Hey, you should let me take that back with me!” I was kidding. He leaned over the railing upstairs with his hands clasped and didn’t say anything.

Ten days later I was putting on my shoes, getting ready to leave, the guitar in the same place. My dad was leaning over the railing again, hands clasped. I stood up. He gestured at the guitar with his chin and said, “Take it.”

It’s an old guitar, now. It has a peculiar internal resonance, as though it has a small concert hall inside of it. I try to bring that quality out by stringing the guitar in double courses. In other words, instead of stringing the 4 lower strings with octave courses, I string them in unison. It makes it a lot harder to play, but with double courses I can draw out overtones if I’m willing to really physically engage the strings.

The frets on my guitar are worn almost flat. There are some tiny intonation issues and places where strings buzz against frets. I took the twelve-string to Ron at St. Paul Guitar repair. He looked the guitar over. He picked up the guitar and sighted down the fretboard. He said, “The frets are flat. There might be some buzzing or intonation issues. Do you like the way it sounds?” I said, “I love the way it sounds.” He handed the guitar back over the counter to me and said, “Then I won’t fix it for you.”

I try to play the guitar for one or two hours before recording. It seems something needs warming up. Maybe the back of the twelve-string needs to be physically warmed up, or my fingertips need a certain pliability. At some point the guitar settles down and the little concert hall inside opens for business.

I like the physicality of playing 12-string. I don’t use a pick. If I’m drifting off to sleep at night and feel my fingertips throbbing I know I had a good day.

Dead Strings

Sometime in the 70s a friend of mine (and Leo Kottke’s soundman) called me up and told me to come over to his house. He and Leo had just finished a tour and he had Leo’s guitars in his front hall. He said, “You can play them if you’re careful.” I zoomed over. The action was very high on the two twelve-string guitars and the strings were dead. It sounded like Leo. I decided then and there that I would make dead strings my sound. If you get used to the bright, ringing tone of new strings, you’ll have to change them all the time. Dead is better.

Kawai Piano

I bought a piano, a good one. I took piano lessons at MacPhail Music School with Susana Pinto.

Susana is from Portugal. She had me learn scales, Bach’s “Inventions” (impossible) and Bartok’s “Mikrocosmos” (possible). She’d listen with her arms folded while I played that week’s lesson. Sometimes she would wait a moment after I’d finished and say, “Steve, I am not convinced.” More study. Susana taught me about voicings. I’d never thought about voicings: piano, guitar, or anything.

I stopped taking lessons but I still heard Susana. After listening to a mix or a new piece of music I’d recorded I’d sometimes hear Susana’s voice saying, “Steve, I am not convinced.”

The piano is a sort of gamelan. A row of gongs. Gong cycles were part of the sonic landscape when I worked in Bali and Java. In performances of Wayang Kulit everyone could feel the big gong coming, the one that marks the beginning of a new cycle. It always felt like the crowd exhaled at the same moment that particular gong was hit. I could use the piano like a row of gongs and let it cycle through the structure of a piece of music.

Mixing

The small concert hall in the guitar encouraged me to seek out a large concert hall to mix the album in. The Macalaster College music department kindly let me bivouac in their concert hall for an evening. I set up two pairs of mics: one in the center of the hall, and one pair in back. It worked well to allow a room’s ambience to settle around the piano and percussion. The natural acoustics of the hall helped the guitar settle into the piano.

More Titles

Spencer came to visit and brought a book of palindromes, “I Love Me Vol. I.”

There were some good candidates for titles: Aerate Wet Area, Ark Okra, Dracula Valu-card, Noise Lesion, Pull Up if I Pull Up, Retro Porter, I Did, Did I, Enrober Reborne, and Señor Drones.

I ran the titles past Michelle Kinney when she came over to record cello and drone parts. She had a look at the list of titles and said, “Too Frank Zappy-y.” What to do? I’d run out of Sanskrit charnel ground names, and proper names seemed too cute by half. I submitted two sets of titles to ECM and tried to forget about it.

The End

I still think in terms of albums, even in terms of album sides. I lined up the songs, left to right, and worked with the running order until it seemed to hang together or make some sort of story. I played the ending of every song with the beginning of every other song until a plot started to reveal itself (this is what happens when you work alone—musical plots reveal themselves). Here’s how it ends: The kids went to college. Their parents were sad for a little while, then fine. Ellen lived and is in complete remission. Grandma died. Grandpa was sad. Everyone else lived as happily ever after as could be expected.