Transplant

My sister had ovarian cancer. I gave her a stem-cell transplant and sent my family daily emails during our time at MD Anderson Medical Center.

(Prologue: Photo number 4--from the apheresis series, at the end). Joe says, "Place your attention elsewhere," while he jams a large-bore catheter in my right arm. Can you see in the photo just how skillfully I'm directing my attention elsewhere?

Houston 01 Arrival

I'm in the apartment in Houston. All well. Ellen is fine. We had a beer. We're "hydrating", in Ellen's words, in order to get ready for our blood draws. I'm getting all the information. We’re in the apartments set aside by MD for things like this and we’re sitting at the kitchen table.

The risk is this: either she does chemo on and off for a few years and dies, or we take the risk of GvHD in this clinical trial, a condition that may arise this summer. Graft versus Host Disease. That's where she gets my stem cells transplanted into her and instead of recognizing her cancer cells, my stem cells see her body itself as being the invader. That's the risk. Then there's GvT. That's graft vs. tumor effect, and that's what we want. The graft (me) goes to war against her tumors, after her immune system has been more-or-less carpet-bombed with the intensive chemo she’ll do just prior to the graft. Plus, Ellen just told me that we want a little bit of GvHD, so my cells recognize her cancer cells as "wrong." If I was an identical twin there wouldn't be enough of a difference in t-cell and antigen makeup.

Houston 02 Prognosis

Elly is about 115 pounds at this point. She is worried, but not worried so much about dying. Normally, most patients in her situation would endure chemo over the next two years and then to palliative care and hospice. But this clinical trial gives her the option of rolling the dice with my immune system. The risk is not so much that her body will reject my graft, but that, since she won't have an immune system, my transplanted immune system will regard her body as a foreign object; something to be killed. So she's worried about how I'll feel if and when I execute her by transplant. It happens, apparently, and there are psychological repercussions between donors, families, and patients. I'll find out more about that this afternoon, at the "family and donors" meeting. I have already promised her I will not feel bad about things going south, if they do. I said, vehemently, that this was the right thing to do and I want to do it, and the other choice is a lousy choice, and she believed me when I said that.

So that's all for now. She's getting a CT scan right now.

She really hates it when people ask, "So, what's the prognosis?" To her it means, "So, when are you going to die?" I guess that could be seen as the underlying question.

Last night she did an impersonation of Andrea, the transplant coordinator I spoke to on the phone from New York that had me laughing very very hard. Ellen is such a relentlessly alive person I can't imagine her absence.

Houston 03 Bloodwork

It's Monday, and I'm waiting to have my blood drawn. Waiting for Laverne, according to the check-in people. Elly and I waited for what seemed hours in the waiting room trying to identify which person in scrubs bursting through the swinging doors would be Laverne.

Laverne came out and asked loudly for Stefan Tibet. She walked me over to apheresis or something, where they had me fill out a 200 item questionnaire, questions I believe I surely should have been asked when I called from New York and spoke with Angela, the other transplant coordinator. Pithy questions wondering whether I'd had sex with a man, even once, in the last year. Or whether I'd had intimate contact with a smallpox scar or scab, even once, in the past three months. I was nervous. Should I answer in the affirmative when asked if I have been in Europe, even once, in the past three years? I answered all truthfully and passed.

Next was diagnostic. They took 11 vials of blood. They asked for a urine sample. I delivered the sample to the nurse, the cup full and warm, reminding me of the time In Nepal when I was dispatched from Boudha to Kathmandu with the students' morning bowel movements in plastic film canisters. Samples. For the clinic. To see if they had giardia or dysentery. Except by the time I got there the student name labels had all fallen off. Due to the taxi bumping down the rutted lanes, or the warmth of the little black film canisters. Or both.

Now we're in the Anderson Café. I had to sit down because I felt like fainting. Elly went to get food.

There's a lot of suffering in this place. People missing hair is the least of it. I saw a guy missing half his jaw a few minutes ago, and the man ahead of me leaving the blood draw room said, "Ok, bye-bye" via one of those buzz-boxes that's used when they take your vocal cords out. What a rotten diagnosis that must be when the doctor strides into a room somewhere, sits down slowly and says, "We have to take out your voice box." Or your jaw.

Now we go to the "family orientation."

OK, family orientation is over. There were five people in the room. The nice lady with hair like a ship stood at a podium. She used the phrase "your cancer experience" many times. She wished us luck on our journey. She told us the class on Bowel Management was limited to 15 participants. That seems wise.

Houston 04 Doctor U

Here's the report:

Every day the shuttle takes us past a large flat adobe-colored wall that has water cascading down it. One of the many M.D. Anderson fountains. Ellen turned to me and said, "Mom looked at that and said, 'hmmm...waste of water.'" So that's what we say every day now when we go past it, and all the rest of you must continue this tradition.

We got up early and went to Ellen's appointment with Dr. Y. A female. Dr. Y is about 39-ish, heavy on the makeup, slightly tan, sleeveless tight dress to show off her totally buff bod. She lifts weights. She runs marathons. She's divorced. She's all business. We met in the conference room after Ellen's examination. Ellen's scan showed that she's in complete remission. Again. Dr. Y reminded us that all second remissions end. 100% of them. 93% of those second remissions are shorter than the first ones.

Then we went to her bone marrow biopsy and ophthalmologist appointments. Both determine a baseline for the Graft vs Host Disease, or, on the other side of things, the Graft vs Tumor Effect. The bone marrow people put her under sedation and yanked a hunk of bone out her hip. She came out in a wheelchair and said, abstractly, "Oooh…what a great drug. You should ask for it." I asked her what it was, and she mumbled that she didn't know. Out of it. I wheeled her down for lunch at the Anderson Café, which I'm already tired of. I'll be gone in a couple of weeks. Ellen, on the other hand, will be here for 3 more months. Many months of that café.

Now we're at the eyeball place. Elly got her eye drops put in at the ophthalmologist, and pretty soon they'll stick pieces of paper in her eyes to measure her tear production baseline. She just looked at me, and her pupils are huge. Her eyes are big black marbles.

I will meet with the legendary Dr. H tomorrow, and have been working on my questions for him. After that I learn how to inject myself with the massive amounts of Neupogen this clinical trial requires.

Here's my list of questions for Dr. Jesus:

1. Allogenic transplants: can it be done again if the effects of this one wear off?

2. If so, can we bank more of my stem cells in case I'm hit by a car in St. Paul? When could we do that? Do I need to keep time free?

3. What would the manifestation a severe GvHD disease response be like?

4. Do I need to keep myself ultra-clean and free of pathogens prior to my draw?

5. What aspect of my stem cells will go to work on Ellen's cancer?

And that's all for today. Tomorrow we start extracting me. Fun! I am really nervous about all the blood they took; that they might find some stupid bacterial infection I picked up in Nepal 24 years ago. The doctor will come in with his sad-faced-doctor look and say, "We can't do the procedure."

Houston 05 Paper

Busy day. Lots of paper.

We went to the stem cell center for my 9AM with Cathy. Cathy is a nurse, or an assistant, I don't know. She's large, red-haired, and has a button on her green scrubs that says "Cancer Sucks." She came through the swinging doors and said, "Stefan Tibet.” Both Ellen and I got up, and she pointed to Ellen and said, "Not you." This was repeated all morning by Dr. H, Tobi, and someone else. Not you. Just me. Confidential. I was signing paper and getting the same rundown, different versions, and being asked, gently, if I was being "coerced" into donating. Also if I had any diseases or tattoos, or had sex with a man in the past three years, even once.

Dr. H is in charge of the blood draw. She felt my lymph glands. She looked at my hands and said I had "great veins." Good.

Tobi asked the same questions, and, like the others, listened to my chest with a stethoscope while I breathed deeply. She had me pull up my shirt while she checked my internal organs. She put two fingers on the area around my appendix and hit them with the same two fingers on her other hand. I said, "What was that?" And she said, "Checking your spleen. Really." Tobi had a mask on. She apologized for the mask, and said she had a cold that day. It's hard to read the face of someone when you have just eyes and a green mask to look at.

Tobi sat down asked about my medical and drug history, and, in the interest of hewing to Ellen's admonition to "be honest about everything" I paused briefly after quickly detailing my life with pot, nicotine, hash, speed, mescaline, and LSD. I paused, and Tobi looked at me like she knew I was pausing because I knew she knew I was lying about whatever, something, possibly the three months I spent at the Dirty Needle Hotel in Hong Kong. Because I'd paused and I couldn't read her face because of the green mask I started blushing, and I hate that and was pretty sure I'd blown it. But I said (after the pause, and thinking quickly) "absinthe." I had to come up with some word to explain my pause, and I remembered the bar in New York in Chinatown that Keith and I went to two weeks ago called the Apotheke. Right, an absinthe bar. So that covered me. Pot, mescaline, LSD, speed and...absinthe. To brighten things up I said, "Absinthe makes the heart grow farmers." (Get it?)

So then the legendary Dr. H came in the room I’d been parked in all morning. I believe he grew up and studied in Shanghai. He came in the room, gave me a once-over and said, "You sure Ellen's brother!" He shook my hand. He gave me the rundown. He said my blood would be corrected on Tuesday. I said, "What?" and he said, "It will take four hours to correct all the blood we need."

Dr. H took some time and gave me answers to all of yesterday's questions.

Briefly: Yes, the allogenic procedure can be done again if this one doesn't work or runs out of gas. He said there are so many variables it's like planting a tree and asking the tree-planter where the biggest branch will be. There will be lots of branches in this procedure. It's immensely complex.

Yes, there are side effects to Neupogen, but they are mild. Only one in a million donors sees their spleen explode. Usually just tired bones, nausea. That's all. This is much much more Neupogen than usual, however, so there are some unknowns and lots of paper to sign.

Yes, they could bank lots more of my blood in case I get creamed by a Humvee in St. Paul while riding my bike. Yes, they get this question a lot at the transplant center, and they do have a look at the actuarial tables as they devise organ storage facilities. I said, "I would be happy to stay here longer or come back on a moment's notice if you need more stem cells." He paused, looked straight at me, and said, "I will remember that."

I asked him how the pathology of a negative GVHD reaction would manifest and he said Ellen would get a rash over her entire body and lose the lining of her gut, then die. That would be a severe case and it would happen in July, when Dorothy is down here. Prior to that she would be treated with cortical steroids, probably prednisone, if I remember correctly. They do want a bit of GVHD reaction, a little rash, just enough so her new immune system (mine) is annoyed with her cancer cells. Her cancer cells will be attacked by either lymphocytes or what he called "NK cells." Natural Killer Cells. He said they don't know for sure how this works. Thus: clinical trial.

My last question, who devised the clinical trial? He did. Now, I know we all want to make our doctors into super-beings, but in my 15 minutes with him I felt like he knows what he's doing, he's got a real fire in his belly about this trial, and he's quietly thinking about this, all the time. As Ellen said later, when she would email him at 11pm with a question, his answer would come back at 3AM. This is his baby. Stage 2 clinical trial. Here we go.

And so we got the checkered flag, the go ahead for liftoff. All systems go. All my blood work came back perfect. The only thing that was out of kilter was my EKG due to my low heart rate (54) due to my madly working out due to my peasant-level attempt to make lots of Natural Killer Cells. Bloodwork is perfect. I'm a cancer terminator machine.

Houston 06 The Tragedy Game

Nothing much yesterday, just a million appointments. They're all beginning to blend into a haze. Blurry waiting-room memories.

Because we've gotten the green light and are somewhat relaxed, and because we're bored Ellen and I are playing the "tragedy game."

This is how you play: if you're walking up to the Commons or the Mays Clinic, and there's construction happening overhead Ellen will say, "It was such a tragedy." Then I say, "Yes, it was just so sad. I heard that they got the go-ahead and they were all ready and then there was this freak accident." Ellen: "Yes, it's just so sad. A workman dropped a hammer at the exact minute Steve was walking into the Mays clinic and it killed him instantly." "I heard that they were still able to get his stem cells, but it's just so sad." "Yes, the family was devastated."

Or, when we're getting into an elevator. "It was just this freak accident." "Yes, I heard that he was running for an elevator she was already in and the doors were closing and he got in except his head got stuck in the door." "Yes, it's just so sad. The doors closed and the elevator started and she screamed but it was too late, and she held onto his legs and his head came off." "It's such a tragedy. But she tied off his carotid arteries with her hospital wristband and they did manage to harvest his stem cells, and she lived to be 94, I heard." “Yes, I also heard his new CD did really well."

Sorry, we're really bored.

So tomorrow I start the Neupogen. The injections. I'll get up and begin injecting myself as per doctor's orders. I'm going to stay in the apartment. We need groceries but I don't want to get nailed by a car crossing the street. (“It's just so sad. He felt like he just had to go out and get milk.”)

We had a class or seminar or something in a hallway for all the stem-cell people. It was led by Tracy, who started all her sentences with "Um" and ended them with "and stuff." Like, "Um you don't want to bring fragrant soap because if you're in chemo it can ignite your nausea and stuff."

Then we went, as a group, to look at a hospital room. Same rooms she was in before. Bummer. Rooms gathered around nurse stations. Pods. Tracy told us children weren't allowed in the rooms because they are just germ-bombs and stuff. That was not good news for the anxious lady who had been asking lots of questions in the class. She has three children under 8. That hurt.

Then we saw the social worker, Xue, who's primary job was to scan the ground for family land mines that might derail this whole process at the last minute. Xue brought us to a conference room and probed. She understood fairly quickly that we are fine as patient, donor, and mutual caregivers. She said that caregivers need help and attention, too, and towards that end presented me with the choice of a scrapbook kit, a photo album, or a notebook with a pen. I took the notebook. (What would I put in the scrapbook? My blood work printouts?)

Xue was very good and very careful. I can see where she fills a crucial need. Suppose that Bobby has leukemia and brother Jimmy is the best lymphocyte match but Bobby used to club Jimmy with a rake handle when Jimmy was 8, then stole Jimmy's wife when he was 23. Problems could arise at this point in the process, the point where everything's lined up, blood work is done, beds are booked, doctors and the team are poised, and then Jimmy considers the ex-wife and rake handle.

Anyway, that's all for today. Elly had another bone biopsy at 7 this morning and we're in the family and caregivers room again. We're alone in here and she's asleep. Nothing until 11:30.

Houston 07 Pre-game

Nothing much, again. It's like a job now. Ellen wakes me up at 6:30, I slug down a cup of coffee, jam syringes of Neupogen in my belly, and then we go wait for the 6:30 shuttle.

We were there at 7:15 for blood draws. We went up when we were called and the lady at the desk handed us our blood labels. These are the labels meant to be affixed to the various vials of blood to be drawn, notating whatever analysis is required. These labels are pleated and folded together. I let mine unfold; I had 5. Ellen had 20. Even the phlebotist was impressed with 20 labels. One phlebotist told Ellen, on finding a good vein, "You got a pipeline there, baby girl."

Then Elly went off to have her plug put in her chest. She was out of it and in a wheelchair when I went to retrieve her. She was due for a chest X-ray and I was due upstairs for the results of my blood work, so I was sort of nervous wheeling her around and I smashed into a bunch of things. Ellen, even in temporary residence on the dark side of the moon, noticed my bad driving.

(Everyone: remember to always back the wheelchair into elevators. Don't wheel the patient so they end up facing the back of the elevator. Bad manners, and impractical.)

I left her at the X-ray station. I went up and got my blood work. Yay! Neupogen worked. White blood cell count up to 40. Normal is 5. Spleen didn't explode. All systems go. I was skipping down the hallway.

I went back down to get Ellen and wheeled her over to the Mays clinic trolleys. Nuclear medicine, two visits, one hour apart. Bone scan. Then lunch in the Anderson Café. Ellen struck up a conversation with the woman at the next table, as she often does. I do like that about this place; we're all in this together. The woman, from Tennessee, pointed out that no matter what happened we were advancing the science. I liked that.

I'm beat. Big day tomorrow.

Houston 08 Game Day

Wednesday. I'm done. The nurse in apheresis just gave me my final numbers and everything looks good. They needed 4 million stem cells and got 11 million, so there's extra to bank for Elly. If I understand this correctly I believe they can hold them frozen for four or five years.

The nurse had me sign out and asked me if I'd gotten my t-shirt. I said I hadn't, and she brought me just about the ugliest t-shirt I've ever seen. Ugly or not, it will be my new Lucky Shirt. It is bright blue, has a picture of two fish swimming, with "We Matched!" and "I Donated!" and "Celebrating Blood and Marrow Donors" in bright orange letters.

Maybe I’ll haul the shirt 18,500 feet up Mt. Kailash. I’m going to try.

(note—4 months later: I did. Photo at the pass, 18,490 feet)

At one point I was waiting in the apheresis lab with another guy who I assumed was a donor because he was youngish, chubby, and florid. Reddish. Lots of blood. Healthy looking. The nurse gave me my shirt, my numbers, shook my hand and said, "You can go now Mr. Stefan Tie-bet" and this guy stood up and said, "Are you a donor?" I said that I was, and asked if he was as well, and how it had gone. He said he had donated yesterday, and had burped out 5 million stem cells. (I didn't parade my 11 million total, but maintained noble silence). We shook hands for about 5 minutes. I asked him who he'd been donating for and he said, "My brother." Well, we almost started weeping, right there. ("I love you, man.")

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xglqe2UhJME

There was another guy like this yesterday who came into the apheresis lab while I was being set up and intubated and fussed over. An extremely thin and gowned man walked in helped by a very robust man. Ellen, as usual, struck up a conversation with the large man, who looked over at me and then walked over with Ellen. He was tall, middle-eastern, expansive, unshaven, royal. Anthony Quinn. Big face. Big smile. Ellen said, "He's come over from Lebanon to donate." We made small talk about Beirut. As much as I was capable of. I gestured to his wan companion and said, "A relative?" He looked into my eyes, smiling, and said, "My brother." He held my gaze. A nice moment. Ellen told me later that he had been the only one out of ten siblings who had matched his brother.

It's now 6:13 pm, and time to take Elly to the hospital. She starts chemo tomorrow, they kill her immune system, and she gets the transplant Wednesday.

I'll try to email once more, but this should wrap things up from Texas for me, for the most part.

Love from Houston, and over to you: Dorothy-caregiver!

Steve

Two Months Later, From Dorothy

Subject: Houston 38

Hi all,

It’s getting hotter in Houston, if that’s possible. It hasn’t rained in a while. My first week we had a couple of good downpours. Wish that would happen again.

For Ell, the days need to be planned around her infusion. She hooks herself up and is then tethered to the backpack (which holds the fluids) for 3-4 hours. Yesterday we did a big grocery shopping early so she could get back and infuse before it got too late in the day.

I feel almost completely assimilated to the routine here now. It will be strange to leave. I will be so relieved when Ell gets to go home too. She’s not ready to go yet, and I can understand why they require the long stay. If things stay on track, she will get to go home on schedule at the end of July.

Tomorrow is day 60 post-transplant. The creature Ellsteve is 60 days old.

Love,

Dorothy

Apheresis Gallery

Here’s the apheresis photo essay, photos by Ellen.

Photo 01. Me on Bed One. I'm happy. I'm wearing Tony's lucky shirt. Joe is happy. Joe's real name is "Josis," but he introduced himself as Joe. I think he's from the Philippines. Joe is the number one guy for running this machine. Joe told us two jokes, one about an atheist and a bear, and the other one about why, for women, men are like parking places.

Photo 02. That's the machine, and the bags in waiting. The stem cells will go into the hanging bag with the label on the left. The other bags give me saline in the return process "so I don't go into shock," according to Joe. The machine removes and returns all my blood three times over 6 hours. It spins the blood in a centrifuge, separating the red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets, and plasma. That's the order, heaviest to lightest. I'm happy in this photo because I'm thinking about living my dreams.

Photo 03. Joe is tying off my right arm. I'm squeezing the two squeeze things he's told me to squeeze. Veins filling and plumping up.

Photo 05-6. Tran is trying to find a place to stick another large-bore catheter in my left arm. Tran is apologizing continually through this process. I am not living my dreams.

Photo 07. I give the thumbs-up. We are good to go. Start the machine.

Photo 08. When I become bored or lose faith I tune to channel 3 on MD Anderson Cable and watch this guy with the hat talking about My Cancer Journey.

(Five hours later.)

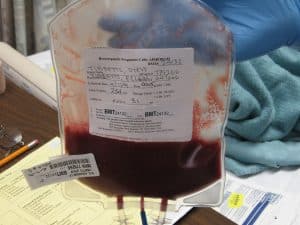

Photo 09-10. Joe shows me the bag with my stem cells. He says, "You are Steve Tie-bet and Ellen is your sister?" I concur, and he initials the bag. The deal is done. I am happy that they will soon take these large steel things out of my arms. Joe has been there for four hours, continually, except for a bathroom break. I had a bathroom break, too, sort of, but I won't go into that. It was complex.

My bloody valentine.