Music and Trance in Bali

By Steve Tibbetts

Special to the Minneapolis StarTribune - May 4, 2003

Photos by Megan Yalkut

(Original article here)

Some years ago I took a group of students studying abroad to an Odalan, an annual, daylong ceremony at a temple in Bali. Only priests and villagers were allowed into the inner part of the temple, but one of our adjunct faculty, Degung, had promised to get our properly garbed group in later, after the trance had started.

“You want to see trance, right? The great Balinese freak show,” Degung said.

After a good three hours in the blazing sun we saw the gates open and villagers in trance being led out to circumambulate the temple. I’ll never forget the look on one young Balinese woman’s face: an incredible mix of astonishment, grief and transcendence.

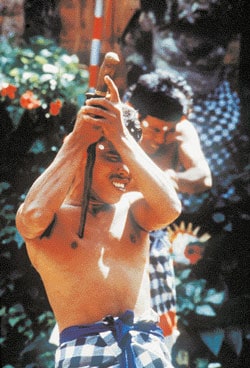

We followed the crowd into the inner temple and stayed five hours. The scene that burned itself into memory was one in which a young Balinese man in trance, facing a row of mute priests, drove a dull kris knife into his chest, rotating it in slow movements while moaning / shrieking / ululating / singing.

The music that brings on this sort of trance is represented on Nonesuch’s series of Indonesian recordings. Some of the best are by the eminent musicologist Robert Brown, who coined the term “world music” back in 1962. Brown leads student workshops and tours in Bali and Indonesia and maintains a residence there.

Brown has been around the block. Just in passing, he mentioned during a recent phone conversation that in 1959 he was in northeast India, researching music, when the Dalai Lama fled Tibet. I asked him if he had seen the Dalai Lama.

“Oh yes, sure,” Brown said. “The whole troop on horseback. I was visiting some almost totally isolated monasteries on islands in the Brahmaputra River, where joyful monks, donated to Krishna by pious families before the age of 5, spent the day singing, dancing, drumming and working in their gardens.

“It was a happy coincidence to be there when that line of men and women arrived on horseback. I remember the date well: It was my 32nd birthday, April 18, 1959. There were some reporters covering the event, and I remember one, probably under the spell of ‘Shangri-La,’ saying, “See that old woman, I’ll bet she’s at least 200 years old!”

Here are Brown’s responses to some questions I asked him in March. He spoke to me by phone from his home base in San Diego.

Q: A friend of mine who’s a frequent visitor to Indonesia said the Balinese recordings had a lot of taksu. What’s your translation of that word?

A: I feel a little inadequate to translate that properly. I suppose it could be “charisma” or some kind of spiritual power. One very powerful dalang [shadow puppeteer] I knew transferred his taksu just before he died. Not to his son, surprisingly enough, but to his great-grandson. I was there for the ceremony, a beautiful ceremony welcoming the spirit back to the family. A little boy, 1 or 2 years old.

Q: Do you see some correlation between the cyclical nature of their music and life ceremonies?

A: My old friend Nyoman Wenten’s grandfather was a dalang who lived to be almost 100 years old, or maybe a little more. Nyoman Wenten is the head of world music at California Institute of the Arts, and a performer of Balinese and Javanese dance and gamelan. He and his grandfather were always very close. [The old man] told Nyoman, who often goes home to Bali in the summer, to be there on a specific day the following summer. Wenten understood what that meant.

On the appointed day the old man, with some difficulty, bathed himself, lay down peacefully on his bed and died. Older Balinese know how to do that. Because he was not of high caste, the old man was carried to the cemetery, about 10 minutes’ walk from the house, in a rather plain coffin with just one roof over it. Kings get 13 roofs.

What surprised me was that Wenten actually climbed up and sat on the white-shrouded corpse, as the procession left for the cemetery. I suspect that he did this to protect his grand- father’s spirit, in an unusually vulnerable state while still associated with the husk of the body before its release by fire.

In Bali, the body is simply something to be disposed of as soon as possible, having served its purpose as a temporary home for the spirit, which is released by the ceremony to fly away, ready to return as part of the next cycle of rebirth.

Balinese live in an interlocking complexity of cycles, including 10 different lengths of weeks, and this is mirrored in the cyclical nature of the gong patterns, wherein gongs of different size and pitch maintain a repetitive and interlocking alternation of sounds.

Unlike much western music, there is no ultimate goal for Balinese melodies, and the final gong in a cycle simply closes that cycle for that particular moment in time. Some Indonesians believe that all music exists in perpetuity, and that all one does in performance is simply to “bring it down” into audible range.

Q: What’s your take on the artistic influence of Westerners who took up residence in Bali in the 30s?

A: I tend to think of Bali as about as complicated a culture as you can find. They take things in, and don’t take other things in. Their culture is like a lodestone; the Balinese will never be anything other than Balinese. The music they do for the tourists is not different from what they do in the temples.

The basic sound of the Kecak, for example, is something that goes back into the past, it’s part of a ritual.

The monkey chant

The famous Kecak chant of Bali dramatizes the section of the epic South Asian poem the Ramayana in which the monkey god Hanuman marshals his troops and attacks the evil King Rawana. Its interlocking rhythms - and the interlocking rhythms of much of Balinese and Javanese music - have influenced composers as notable as Steve Reich and Philip Glass.

The Kecak came into its pre- sent form in the 1930s, when a Balinese dancer was encouraged by Walter Spies, a German living in Bali, to adapt an ancient form of chanting for a tourist performance.

Tourist music or not, the vocalizations and rhythmic acuity of these groups are astonishing. Of the two Kecak CDs on Nonesuch, Golden Rain better captures the insane, hell-bent quality of this music. The more recent CD Gamelan & Kecak is a better all-around recording.

However, neither can supply the unearthly torchlight they use for the performance, the bugs humming in the background, the masks, the dancing, the chanters swaying, the upthrust arms, or the 99-percent humidity. You’ll just have to go there for that.

In some ways the tourist industry has invigorated Bali’s music scene. Your basic savvy traveler wants to see the best, and Bali will try to oblige. Ensembles meet for competitions in order to determine which village has the “No. 1 gamelan ensemble of Bali.”

Three or four ensembles will set up in a courtyard and play simultaneously and deafeningly, trying to throw the others off. It’s sort of like sumo wrestling, except with sound.

‘Big mice’

Tourism to Indonesia is down, as you might imagine, and even a cursory Internet search found round-trip flights from Los Angeles at about $800.

Start by buying a map of Bali. The island is shaped roughly like a heart with volcanos in the middle - which is fitting, somehow. After getting to Denpasar, head upcountry to Ubud, and stay there for a month or two. You’ll make lots of friends (they’ll find you), and with their help you’ll penetrate the Bali theme-park tourist veneer. It’s also possible to get a cheap flight to Singapore, where you can get a cargo ship from Tanjunpinang to Jakarta, and from there take the train and ferries across Java to Bali.

My wife and I signed up for deck space on a cargo ship and were ready to go when the deck master asked us if we minded the “big mice at night.”

I said, “Big mice?” The man held his hands about nine inches apart. My wife said, “You mean rats?” He said, “OK, rats.” We took a plane.

Barring a trip to Asia you can engineer a total sense immersion in the comfort of your home. Get one or two of the Nonesuch CDs: Java: Court Gamelan or Bali: Gamelan & Kecak are good places to start.

Then move your stereo into your bathroom, release 37 frogs and 100 crickets, run hot water until it’s nice and steamy, light a clove cigarette and start playing the CDs. Turn the shower on and off to simulate falling rain. Arrange for an occasional earthquake.